Your Interfaith Love Mentor Will See You Now

The India Love Project wants to become a forum for would-be interfaith couples to get advice from those who’ve done it. Could an act of mentorship save lives?

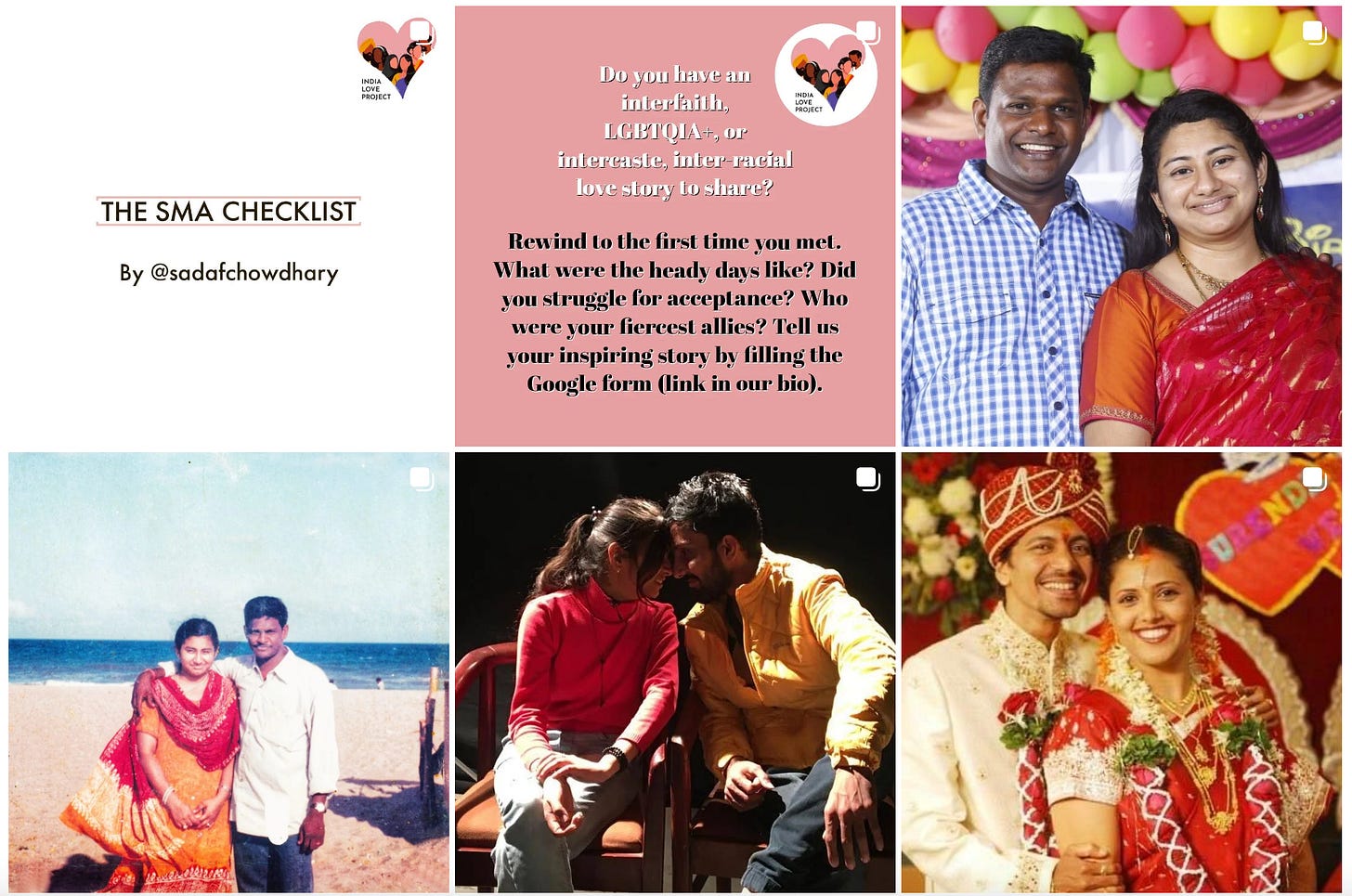

The India Love Project is the sort of instagram page that makes you feel optimistic about the future.

Founded 3 years ago by journalists Priya Ramani, Samar Halarnkar and Niloufer Venkatraman, the page features stories of real couples in relationships considered taboo by much of Indian society— interfaith, intercaste, LGBT+ — who are making their love work. Ramani says the page was inspired after a jewelry ad featuring an interfaith couple was targeted by social media trolls. The company, Tanishq, rescinded the ad “for the safety of its employees.” The India Love Project launched on Instagram a few weeks later.

The page now features more than 500 stories. That might not seem like much in a country of 1.4 billion people. Many of the couples featured do not reside in India, which Ramani tells me is a big reason they feel safe enough to post their faces in a country where interfaith couples have been targeted for violence. (Generally, the couples featured in ILP have higher-than-average income and education, because privilege can also be a shield.)

But under the surface of this elite celebration is an ocean of DMs from people who wish to join the club. Younger, less resourced, more vulnerable - they have lots of questions, whether practical - anyone know a good laywer in Chennai?, or metaphysical - How can I be sure he is the One? But the most common question, according to Priya Ramani, is: How do I tell my parents?

And how do you answer that?

Sadaf’s story

Sadaf Chowdhary never expected to be in an interfaith relationship herself, let alone become a mentor to others. She grew up in a small town in India to a conservative middle class muslim family that valued her education. She graduated law school and found work at a law firm, where she met Yatin, another lawyer. He is Hindu. Dating across faith was “an alien concept,” she tells me. None of her friends or even anyone she knew was in such a relationship. “The only [interfaith] stories we knew were from Bollywood.”

Sadaf describes her hometown as the kind of place where “if I am bringing a guy home, everyone in my neighborhood knows that Sadaf has come home with a boy. Right? And if word gets out that he is a Hindu guy, maybe my parents are okay with it, but what if someone else takes up on his ego and says that, no, no. How is this possible?”

Sadaf was not worried about violence from her parents (‘soft-spoken,’ ‘educated’) but when it came to the community she wasn’t sure. As a precaution, when Sadaf went home to tell her father about her new boyfriend, she brought two friends along. Her friends’ presence made her feel safer. So did her lawyer’s salary. “Had I gone home when I was 22, with no job, just fresh out of college and said, I want to get married, probably my dad would've put me under house arrest and gotten me married to someone within the community.”

Talking About Honor Killings

Since reporter Lauren Frayer and I started discussing the Rough Translation podcast series Love Commandos, and then as others joined us in the edit room — Adelina, Miranda, Mansi, Ariana, Parth, Raksha, Luis and many others — we have had a running debate about violence. The debate goes like this: the Love Commandos would not exist if honor killings were not a reality. The couples that you meet in the series seek refuge in the shelter because of a genuine fear that they or their beloved will be killed by their families. At the same time, honor killing is quite rare. It is the most extreme consequence that can befall love couples, and some accuse Western reporters of over-emphasizing extreme stories. When I launched Rough Translation six years ago, I conceived of it as a show that would question conventional media narratives, not parrot them. So how should we talk about the violence that love couples fear and face in an honest way?

The fact that Sadaf successfully mitigated her own vulnerability doesn’t make her experience less scary. Violence can shape our choices even when its likelihood is low. (A few weeks ago, I posted about the novel Teen Couple Have Fun Outdoors by Aravind Jayan, where physical violence against the young lovers never occurs but always lurks menacingly in headlines and family histories.)

Sadaf’s mission home succeeded. She and Yatin married. Now came the confusing part: The pointed questions from acquaintances at parties. The fraught interactions with in-laws who seemed to interpret Sadaf simply doing things “her way” as a rejection of Hinduism itself. The burden of expectations that the newlyweds put on each other, as they felt they needed to justify their choices by performing being head over heels in love in public. Sadaf was now “safe” from violence but she felt lonelier than ever. “It is very difficult to carry on with your professional commitments, to carry on with your day job, and also to carry this burden of emotional blackmail [from] your own family,” she says. “If I had someone to talk to at that time, maybe I would have had clearer perspective about life in an interfaith marriage.”

Maybe the problem with media stories that focus exclusively on the threat of physical violence is not that we exaggerate the risk, but rather, that we underplay these other sorts of pain - the pain of rejection, scrutiny, recrimination - that can follow in its wake.

An Instagram Mentor is Born

When Sadaf posted her story to the India Love Project, she was looking for a salve to loneliness. What she got, at first, was hate. She considered making her account private. But she realized that for every troll, there were even more people who were seeking out such stories and wanted to speak to someone who had been in an interfaith relationship to see “what their life is like.”

Now, the more she posts, the more DMs she receives, most often from young Muslim women either contemplating or involved in relationships with Hindu men. How has life been for you? Did you convert? What support did you expect from your husband? And always: how do I tell my parents?

“I don’t give them advice,” says Sadaf, and then proceeds to dispense what sounds very much like advice (she prefers to call it counsel). Financial independence is key. Don’t convert unless you want to. And when it comes to parents, “are you at the risk of honor killing?” If there is even an “iota of doubt” where you feel like you could be beaten up, or physically restrained, or your partner could be hurt by your family, or vice versa, “then you should have enough funds to be able to move to another city at a moments notice.”

Violence, at a Distance

Sadaf’s practical attitude toward the potential of being violently attacked by one’s family feels important to pay attention to, if only to recognize how rarely we read about honor killing in this way. Most often, discussions of honor killing in the media center around implacable Forces of Tradition and the powerlessness of young people - even one’s own flesh and blood! - to stop them. Sadaf’s approach is more subtle. Where and how you break the news to your parents can matter as much as the news being broken. She tells the story of a Muslim woman with a “very strict” and well-connected father who reached out, terrified “that if she took [her boyfriend] home there would be goons and anything can happen, you know?” Under Sadaf’s advice counsel, she decided to break the news about her Hindu boyfriend in a neutral location (a coffee shop in New Delhi) with two of her friends in tow (as Sadaf herself had done). During the meeting, Sadaf and Yatin waited nervously by the phone, like anxious parents, ready to drive to the location if necessary and… intervene? Sadaf wasn’t sure, and thankfully, she didn’t have to find out. Not only did the the meeting go off without violence, but five months later the families are civil with each other. “They don’t go to each other’s houses, the parents, but when they’re at a neutral spot, they meet up, they hang out together…so that’s a win, I would say.”

Can mentorship save lives? At least it can make the journey less lonely. The India Love Project plans to formalize their mentorship project soon. Sadaf is excited to sign up. Whereas she once didn’t know any interfaith couples, now she has four couples she calls friends. As Surya, one of the characters we meet in the Love Commandos shelter, told reporter Lauren Frayer: “Friends are the bones of love marriage.”

Poll of the week

ISO “Travel Agent” - Malaysia and (briefly) Japan

A friend suggested we start a “travel agent” section of this Substack where I seek the collective wisdom of this well-traveled community on places I’m going to. I have no idea if that’s going to work, but let’s give it a try! In September I’m going to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to speak at the RadioDays conference, with a long layover in Tokyo. Who should I try to meet? What should I do? Tell me in the comments and I’ll tell you how it went!

I also live in Tokyo though it’s only been a year and half since we moved. My suggestion is to find something you are a “geek” about (roughly, “otaku” in Japanese). Tokyo is filled with people who love something so much that they have taken it to the extreme to be the best / most knowledgeable at. It could be food, coffee, denim, manga, fountain pens, trains etc. I promise you you will find some place that has spent a lot of time lovingly curating whatever it is you’re interested in.

Thank you for telling us about the India Love Project! It's my favorite account to browse now